The Museum Collections

What We Collect

|

|

|

Tameside Museums Service collects objects which are either made in Tameside or have very strong connections to the area.

Our Social History collections comprise over 16,000 objects relating to the social and industrial history of Tameside. Many visitors are surprised to find out that only a very small percentage of the museum’s collections are ever on display at any one time. The rest of the collection is kept in storage.

We display social history objects on our old street at Portland Basin Museum and we change our temporary exhibitions every six months to enable different objects to be on show. Many large items of machinery are on display in the Industrial History Gallery at Portland Basin Museum, along with smaller items made in the borough.

To enquire about an object in our collection, or if you have an object you think may be of interest to us, please telephone 0161 342 5480 and ask to speak to the Collections Curator.

- Civic Silver

- Costume and Costume Accessories

- Tools

- Domestic Equipment

- Haughton Green Glass

- Radcliffe Collection

- Eli Whalley's Donkey Stones

- Cotton Queen Dress

- Clogs

- Jethro Tinker's Mosses

- Charles Moore Shells

- Jones Sewing Machines

- Williamson Ticket Printers

Reserve Collections

The large collections kept in our museum stores are known as the reserve collections. These can be viewed by appointment. Please telephone 0161 342 5480 and ask to speak to the Collections Curator.

Archaeology

The Archaeology collections include prehistoric tools as well as material from excavations at Staley Hall, Denton Hall, Dukinfield Hall and Haughton Green glassworks. Additionally we hold a small collection of Egyptian, Greek and Roman artefacts, collected by local mill owner Norman Bramley Radcliffe.

Natural History

The Natural History collections include the Tinker collection of Mosses, numerous Plant Specimens, Birds Eggs, theMoore collections of Shells and Molluscs and Jackson and Seth Radcliffe's collections of Geological specimens.

Civic Silver |

|

This impressive collection of silverware has been gifted over the past two hundred years to the nine towns that now make up the borough of Tameside.

The cups, trophies, candelabra, caskets, chargers, maces and commemorative trowels celebrate local events. There are also chains and medallions that were worn by the mayors of each town.

Costume and Costume Accessories |

|

We hold a varied collection of clothes and accessories. Highlights include a Victorian wedding dress, a dress worn by the local Cotton Queen in 1930, a Whit Walks dress, a jacket worn by local mill owner and philanthropist J.F Cheetham, and locally made hats, gloves and various clogs.

Tools |

|

We have a large collection of tools from a variety of local trades including shoe making, printing, hatting, glove-making and donkey stone making.

Many are on display in the Industrial History Gallery at Portland Basin Museum. We also have objects relating to local companies such as Williamson ticket printers.

Domestic Equipment |

|

Collections include Jones sewing machines, washing machines, cookers, mangles and refrigerators, as well as radios, televisions and furniture.

Haughton Green Glass |

|

These objects were found by archaeologists at Haughton Green near Denton in 1968. They come from the site of a seventeenth century coal-fired glassworks that made window glass and vessel glass. Window glass was in demand for the many new halls and farmhouses that were being built at the time.

Making glass vessels was a specialised task which attracted skilled workers. Two prominent Huguenot glass-working families, the Du Houx and Pilmeys, came from France to live here. The black glassware found at the site is of very good quality, pointing to the high technical knowledge of its makers.

The plate, which they would have brought with them, suggests they came shortly after 1615. The jug, bowl and fragments of bottles give us an idea of what was produced at the glassworks.

The glass furnace at Haughton Green was unusual in that it was coal-fired rather than charcoal-fired. James I forbade the use of wood in glassmaking as it was becoming scarce and was crucial to so many other industries.

The deposits of coal in the local area probably attracted the glass makers to this site. The introduction of the large flue system was also a significant development. The increased draught not only enabled the coal to burn better, but also provided the higher temperatures.

This in turn enabled the glassmakers to produce the high quality black glassware, which at the time was unrivalled by any other glass maker in the country.

The site was abandoned around 1650 and there is no mention in the parish registers of glassmakers after 1653.

A selection of glassware found at Haughton Green is on display at Portland Basin Museum.

Radcliffe Collection |

|

A small but fascinating collection of Egyptian, Greek and Roman artefacts were collected by Mr Norman Bramley Radcliffe, a woollen manufacturer from Stalybridge, in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

In 1933, following Mr Radcliffe’s death, his widow donated the collection to the newly opened Astley Cheetham Art Gallery in Stalybridge.

Mr Radcliffe had bought most of his objects at auction. Some came from prominent collectors selling off parts of their collections, while others were sold off by archaeologists who needed to raise money to fund their next dig.

The Roman collection is on display at Portland Basin Museum.

The Ancient Egyptian collection is on display at Astley Cheetham Art Gallery.

Eli Whalley’s Donkey Stones |

|

Donkey stones are part of Lancashire and Yorkshire’s rich industrial history. Made of limestone, cement and bleach, these small blocks were used for cleaning stonework such as flag stone floors, front door steps and window sills.

Donkey stones were originally used in textile mills to provide a non-slip surface on greasy stone staircases. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they were adopted by housewives as the ideal way to keep their front door steps looking like new.

The step would be washed first to remove soot and dirt and then the donkey stone, mixed with a little water, would be rubbed along the edges. "Doing the step" was an ideal occasion for gossip between neighbours, as well as a source of rivalry.

It was not unusual for a proud housewife to clean the pavement in front of the house too! It was a chore often bestowed to children at weekends.

The name ‘donkey stone’ comes from the trademark of a donkey used by Reads of Manchester, who were among the first companies to produce the stones in the nineteenth century.

Donkey stones were very cheap to buy and people often got them free from their local rag and bone man in exchange for old items. The stones came in white, cream and brown, with cream being the most popular colour around Manchester.

One manufacturer of donkey stones was Eli Whalley and Co. which was founded in the 1890s in Ashton-under-Lyne, a few miles east of Manchester. Whalley continued the animal theme, choosing a lion as his company trademark. The inspiration came from his many childhood visits to Belle Vue Zoo.

Eli Whalley and Co. was based on the old wharf of the Ashton and Peak Forest Canal meaning the stone and salt could be delivered by canal boats. The large chunks of stone were crushed in a stone crusher then mixed with cement, bleach and water in the large pan to form a paste.

The paste was then transferred to the work bench where it was formed into a block using the wooden boards and cut to make two and a half dozen stones. Finally the stones were stamped with the "lion brand" moulds before being transferred to racks to dry.

Production peaked in the 1930s when 2.5 million donkey stones were made every year. Placed end to end they would have reached from Ashton to Blackpool and back. Eli Whalley was reputed to have built himself the finest house in Ashton from the profits of his business.

Demand gradually fell over the following decades. The decline of the cotton mills removed the main bulk buyer of the stones and changing social trends meant it was no longer seen as essential to have a donkey-stoned step.

By the time of its closure in 1979, Eli Whalley was the world’s last manufacturer of donkey stones.

A selection of donkey stone making equipment is on display at Portland Basin Museum.

Cotton Queen dress |

|

In 1930 Frances Lockett, a 19 year old mill worker from Hyde, was voted Britain’s first Cotton Queen.

Between 1930 and 1939 the annual Cotton Queen competition was a major event in the cotton towns of the North West. The aim was to revive the fortunes of the once prosperous industry.

Frances spent her year as Cotton Queen traveling the country, promoting cotton at exhibitions, parades and public events. She was treated to champagne receptions and given gifts such as this beautiful beaded dress.

Being the first Cotton Queen was a huge honour for Frances and for the town of Hyde. After being crowned, the town gave her a civic reception, with more than 20,000 people turning out to congratulate her.

After her year of fame, Frances returned to work at J&J Ashton's Mill in Hyde where she worked as a weaver until her marriage to local policeman James Burgess in 1937.

Public interest in her remained high. The whole of Hyde turned out for her wedding and she was constantly in demand for charity events.

Frances’s family donated her dress to the people of Tameside and it can be seen on display at Portland Basin Museum.

Clogs |

|

These clogs belonged to mill worker Laura Owen. Laura started work at Chapel Hill Mill when she left school in the 1920s aged 14. She worked as a weaver at various mills in Dukinfield before retiring in the 1970s.

Cotton mill workers often wore clogs because of the wet floors in the cotton mills. Clogs were traditionally made of alder and were commonly worn by all classes throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

Leather shoes in those days were made by hand and consequently very expensive. They were beyond the reach of working people, especially the poor. A Lancashire Song written just after the Battle of Waterloo includes the lines:

“Aw’m a poor cotton weyver, as mony a one knows,

A’ve now’t to ate I’th heawse, an aw’ve worn eawt mi cloas;

Yo’d hardly gi’ sixpence for a’ aw’ve got on,

Mi’ clogs are boath brosin, and stockings aw’ve none.”

An article by the Amalgamated Society of Master Cloggers cited Dr Arkwright who felt that clogs were vital for cotton workers’ health. He believed “were it not for the extensive use of clogs, especially by the young women in our weaving sheds having to stand on flagged floors, their health would be undermined and they would be more susceptible to rheumatic diseases than they are at present, proving they are greatly indebted to the inventor of this kind of footwear.”

There is a theory that clog dancing began life in the cotton mills as workers tapped along to the rhythms of the loom shuttles to keep themselves entertained during their long shifts.

There are several examples of clogs on display at Portland Basin Museum.

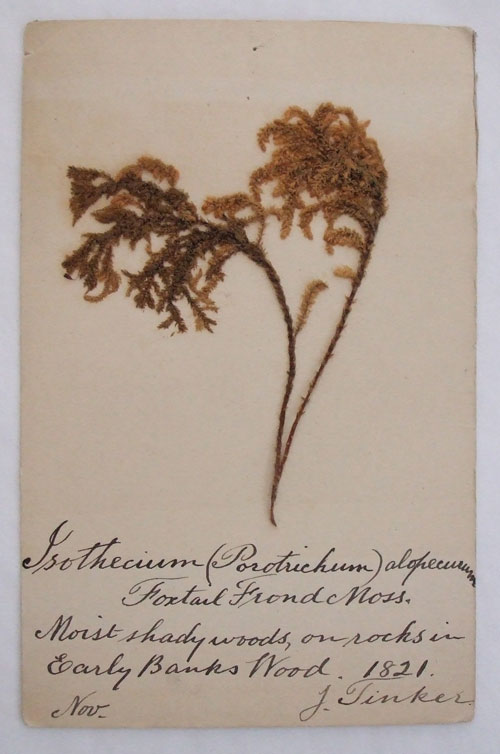

Natural History CollectionJethro Tinker’s mosses |

|

Jethro Tinker was born in September 1788 in a cottage at North Britain Farm in the Brushes Valley high above Stalybridge. Growing up surrounded by countryside inspired Tinker’s early love of nature and in his teens he became a pupil of celebrated local botanist John Bradbury. Tinker worked in the local cotton mills where he progressed from an operative weaver to overlooker and ultimately manager at Cheetham Mills.

Amazingly, the long hours at the mills did not detract from Tinker's enthusiasm for natural history and throughout his life he collected specimens of wildflowers, mosses, insects, moths, butterflies and shells all of which were beautifully collated. He became a familiar figure amongst botanists, especially through his work with the local societies that existed in many towns to promote the study of natural history.

Tinker would often go into the countryside after leaving the mill and he would readily walk twenty miles to areas like Buxton to collect particular specimens. A fond tale of Tinker is often recounted to show his enthusiasm for his studies. In his later years whilst on a march through Ashton after a church service, he spotted a rare butterfly.

Dressed in his Sunday best he tried to catch it in his top hat. Failing the first time, he chased through the crowds for a full two miles until he was finally successful.

In later life, Tinker left the mills and worked as a shopkeeper, a publican and finally as a gardener at Eastwood Park. Today, a blue plaque to commemorate him is sited at the entrance to Stalybridge Country Park.

Tinker’s legacy was the collection of specimens that were left to the museum at Highfield House in Stamford Park. Sadly these suffered neglect over the years and in 1915 were reported to be in a very poor state of preservation.

Today, the surviving collection is cared for by Tameside Museums & Galleries Service - about a hundred specimens of mosses each preserved on a postcard covered with tissue paper and labelled in Tinker's own handwriting.

Charles Moore Shells |

|

Tameside Museums Service looks after a large collection of molluscs collected by Charles Moore (1869-1949).

Moore worked in Wilson and Robert’s office in Millbrook and was also an enthusiastic member of Stalybridge Harmonic Society and St Paul’s Operatic Society.

A friend described him as “sparely built and bearded, he was well known as a somewhat eccentric man who liked to feed wild birds as well as hunt the canals and countryside for shells.” Among his more important finds were specimens of Vertigo Alpestris, the first recorded for North Lancashire, found in 1902.

The specimens shown here are as they were boxed and labelled by Moore himself. He also exchanged specimens with naturalists abroad to build up further his collection of foreign specimens.

In the 1800s there was a tremendous growth of interest in natural history. Enthusiastic amateurs formed societies, sometimes called Linnaean societies on account of their concern with classification.

There were several societies in Tameside, for instance the Ashton Field Naturalists, founded in the 1860s. A description written in 1945 looks back to the 1860s: “to anyone who has never attended one of these working men naturalists meetings it is always a revelation, for here perhaps are 30 or 40 men from the lathe or the loom, taking in maybe a butterfly, a moth, beetle or snail, and describing it as correctly as the most learned professor.”

Over 3,300 little boxes of shells collected by Moore are held by Tameside Museums and Galleries Service.

Jones Sewing Machines |

|

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sewing machines were an important fixture in homes across the country.

There were few clothes shops on the high street and only the wealthy could afford professionally made clothes. Housewives therefore had to make their own clothes for the family, using cotton and threads produced in the local mills.

The sewing machine of choice for Tameside housewives was a Jones sewing machine.

William Jones established the Jones Sewing Machine Company in Guide Bridge, Audenshaw, in 1859. He was the manufacturer of small domestic steam engines before turning his attention to sewing machines. He made significant design improvements to the type being imported from America, and went on to mass produce his machines. Soon, he was able to offer the public excellent sewing machines at very affordable prices.

As domestic sewing machines grew in popularity, Jones’ business expanded. By the 1950s Jones was second only to Singer, the American sewing machine makers, in terms of manufacturing and sales in the UK.

In 1968 Brother Industries of Japan, who also made sewing machines, acquired Jones. In 1976 the firm was re-named ‘Jones and Brother’ and 1996 ‘Brother UK Ltd’. The original site at Guide Bridge is now the headquarters for the European operation of Brother International Europe Ltd.

Portland Basin Museum has a large collection of Jones sewing machines. They range in date from the 1880s to more recent models.

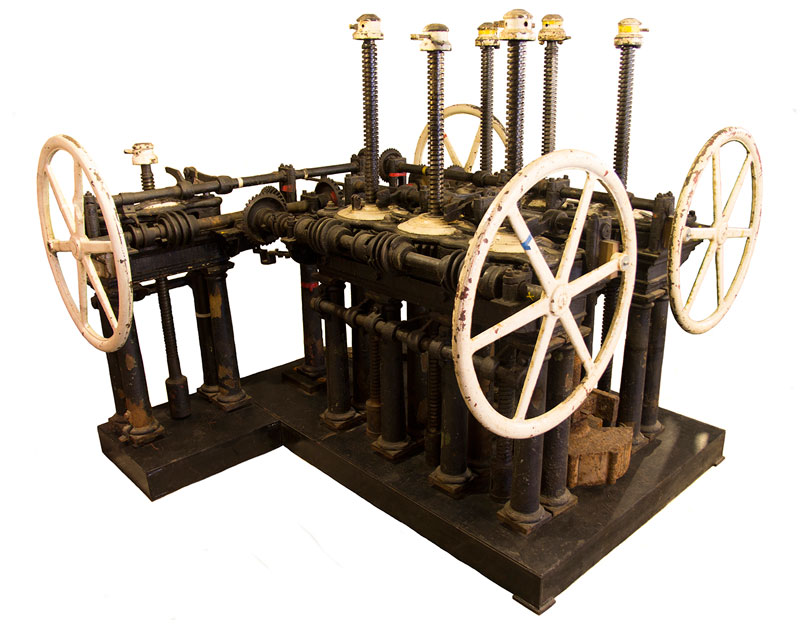

Williamson ticket printers |

The North Mill Ticket Works were begun by John Williamson in 1835.

Initially, the business supplied tickets for local entertainment centres and pawnbrokers.

Gradually, the business took advantage of the transport networks and produced ticket systems for horse trams in Ashton, Oldham and Stalybridge and later the tram and local bus services to Manchester. In the 1920s the company began supplying tickets nationally to ballrooms and cinemas.

This small family business, later known as ‘Alfred Williamson Ltd’, grew into a company which printed tickets and ticket systems for use throughout England and as far away as Iceland and Africa.

The sign which hung over the entrance to Williamson’s Ticket Works on Cotton Street East in Ashton, plus a small selection of objects relating to Williamson are on display in the Industrial History Gallery at Portland Basin Museum.